Imagine you’re a university professor who just finished writing a research paper claiming timber harvest is the leading source of carbon emission in Oregon. You print off your final paper copy, seal up the paper journal submission envelope, and put the envelope in the mail so it can make its way to the publisher in a truck that burns fossil fuels as it trundles across the country to its destination. You’re about to climb into your 2011 Prius to take a much-needed vacation to Yellowstone National Park, but before you shut down your computer (that runs on electricity produced by burning fossil fuels) you decide to calculate your trip’s carbon footprint. It turns out that even in your fuel-efficient vehicle, driving the 3,316 round-trip miles to Yellowstone produces 0.61 tons of carbon dioxide! The good news, though, is that you only need to plant five trees before you leave because in five years those trees will have offset all the carbon emissions from your trip. When those five trees have reached age 40, they will have sequestered approximately 5 tons of carbon dioxide. If those were five Douglas-fir trees, they will have sequestered 69.5 tons of carbon dioxide by age 100! As you climb into your car, you have a nagging sensation in the back of your mind about the paper you just submitted. You feel like you forgot something in your calculations, but you just can’t seem to put your finger on it…

In January 2018, Oregon State University College of Forestry professor Dr. Beverly E. Law and others (Law et al. 2018) published an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) claiming timber harvest is the leading source of carbon emission in Oregon. Though the underlying data are not wrong, the researchers manipulate those data in a manner clearly designed to produce a contrived outcome. Because the assumptions are entirely untethered from reality, the paper is unusable in carbon policy conversations in Oregon.

Analysis: In zeal to restrict logging, advocacy groups exploit dubious research

There are a host of problems with the paper (click here for the top five mistakes) but the paper has one error so enormous you could drive a carbon-packed log truck through it: they completely ignored the fact that the forest sector replants after harvest. That’s like trying to convince Oregonians we’re using up all the water in the reservoir and ignoring the fact that it rains.

According to the most recent USFS Forest Inventory and Analysis data, Oregon’s forests are growing twice as much wood annually than is harvested – in fact, since 1953, the entire U.S. annual net growth has exceeded annual harvest and the total volume of growing stock on U.S. timberlands has increased by 60% (Oswalt et al 2018). More than 40 million tree seedlings are hand-planted in Oregon every year. Not only is reforestation the right thing to do and the only way to guarantee a sustainable, reliable source of timber, but it is also the law in Oregon. Reforestation is one of the many things required by the Oregon Forest Practices Act (FPA). The FPA is first-in-the-nation legislation to regulate forest management and to formalize a way to incorporate best practices and evolving science into an adaptive regulatory framework. It was landmark legislation in 1971 and remains current today, with nearly 40 revisions since then. The FPA incorporates more than 45 years of science to safeguard water, fish and wildlife habitat, soil and air. Not only does the FPA require reforestation following harvest, it also requires that within six years those new seedlings (more than 200 per acre) are thriving and outgrowing competing grass and brush on their own.

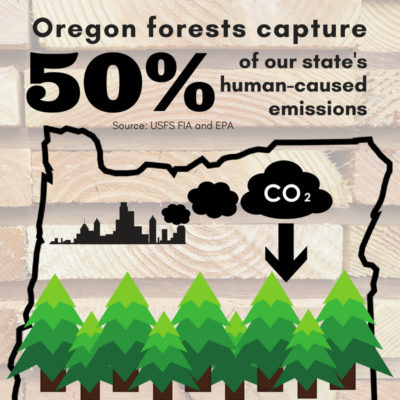

Forest carbon stock and flux data sourced from USFS FIA data (2001-2010) and emissions data sourced from Inventory of US Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks (2015).

Roughly 50 percent of the dry weight of wood is carbon, and that carbon remains locked in wood products produced from Oregon’s forests for the entire life of those products, long after those reforested acres grow into healthy, lush forests. In fact, because one cubic meter of wood stores nearly a metric ton of carbon dioxide, a new eight-story condominium building currently being constructed in Portland (called Carbon12) with extensive use of mass timber products, will offset 577 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions from going into the atmosphere. That’s equivalent to keeping 169 cars off the road for a year — with one building. The newly completed Oregon headquarters of First Tech Credit Union in Hillsboro is the largest known U.S. building to date that uses cross-laminated timber, or CLT, for flooring, and glulam posts and beams. It is five stories and high and has 156,000 square feet of office space. U.S. and Canada’s forests can grow this much wood in 2 minutes! The building stores 530 metric tons of carbon dioxide and avoids 1,130 metric tons of carbon dioxide. This is equivalent to taking 317 cars off the road for a year and saves enough energy to operate 141 homes for a year! Find out the carbon benefits of your wood home based on square footage or board feet associated with construction using this carbon calculator.

Wood is the ultimate green building material because it is the only major building material that stores carbon. It’s renewable, recyclable, and in Oregon, it’s sustainably and locally produced. Wood produced from Oregon forestland regulated by the state’s forest protection law qualifies as responsibly sourced under the internationally recognized American Society of Testing Materials standard, and therefore can count toward the Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED) credit for wood use in sustainable building projects. New houses are built every day in Oregon and across the United States. If we were to reduce the state’s wood production, we only ensure that developers turn to wood from other jurisdictions with more lenient environmental protections than we have in Oregon. Or worse, that we might turn to less climate-friendly alternatives to wood.

Setting aside the fact that not replanting is illegal in Oregon and therefore the Law et al. 2018 scientific model is unrealistic at best, the researchers also cast aside the permanent benefits of using wood over alternative building products, citing a news article (not a peer-reviewed scientific article) that claims modern wood buildings only last a few decades. Continuing in the “alternate universe” theme, the researchers further claim that carbon emissions from wildfire were lower than carbon emissions from timber production. In order to arrive at that conclusion, the publication used outdated fire data and omitted the Biscuit Fire as an outlier, despite more recent publications concluding that fires of that magnitude will be increasingly common in the future due to climate change (Jain, Wang & Flannigan 2017).

Understandably, the publication elicited a lot of head shaking, which enticed Dave Atkins, retired USFS forest ecologist and president of the online news outlet Treesource to take a deep dive into the details of the author’s assumptions. Atkins interviewed better experts than evidently participated in the PNAS peer-review process and wrote an extensive rebuttal piece that sheds light on the significant flaws in the publication.

Wood products come from trees. And there’s no better place in the world to grow (and re-grow) trees than Oregon. A healthy wood products market generated by local, sustainable forest management practices incentivizes good forest practices, maintains the value of forestland, and keeps forests as forests in Oregon. In light of its positive contribution to climate change, OFIC looks forward to working with state lawmakers on finding ways to encourage the use of more Oregon wood, not less.

News

- Working Forests Help Oregon Fight Climate Change, Jed Arnold, Daily Astorian, June 26, 2018

- Analysis: In zeal to restrict logging, advocacy groups exploit dubious research, David Atkins, Treesource, June 13, 2018

- The top five ways Law et al. 2018 got it wrong, OFIC, June 2018

- A vibrant wood products market is good for Oregon and the climate, Kristina McNitt,Oregonian May 5, 2018

- A well-managed forest means less greenhouse gas loose in the environment, Noelle Arena, Register Guard April 8, 2018; Herald and News April 22, 2018

Other Resources

- Forest Offset Projects in a Carbon Trading System, Society of American Foresters

- Dovetail Partners, Carbon 101: Understanding the Carbon Cycle and the Forest Carbon Debate (Bowyer 2012)

- Dovetail Partners, Managing Forests for Carbon Mitigation (Bowyer 2011)

- A real Life Cycle Analysis of forest management and wood utilization on carbon mitigation: knowns and unknowns (Lippke et al 2011)

- International Panel on Climate Change, Ch. 11: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU) (IPCC 2014)

- International Panel on Climate Change, Ch. 9: Forestry (IPCC 2008)

- State of America’s Forests – interactive, maps, graphs & stats – created by US Forest Service analysists, using the most recent USFS Forest Inventory and Analysis data

- Forest Carbon Accounting Considerations in US Bioenergy Policy (USDA USFS, Miner et al 2014)

- Climate change, forestry and substitution of carbon-intensive materials (Gustavsson et al 2016)

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO 2016) – Forests for a Low Carbon Future: Integrating forests and wood products in climate change strategies

- Conclusions and caveats from studies of managed forest carbon budgets (Vance 2018) – metanalysis of tradeoffs and incentives when managing forests for carbon