As the wood products industry and Oregon’s rural communities continue to claw their way out of the Great Recession, a new threat is looming on the horizon. In November, Oregonians will get a chance to vote on Measure 97, the biggest tax increase in Oregon history, a $6 billion gross receipts tax that would affect the forest products industry, their suppliers, and customers. This new tax will put Oregon sawmills at a disadvantage vis-à-vis competitors in Washington and Canada.

The proponents of Measure 97 argue that this “corporate sales tax” is needed so large, out-of-state corporations pay their fair share, but if approved, this tax would reach much further than that. Started in 1942, Hampton Lumber is an Oregon-based, family-owned business but they meet the definition for a corporation that would be taxed if Measure 97 passes.

Hampton’s mill in Willamina.

“This tax would increase costs throughout our production process, from timber harvest to wholesale,” said David Hampton, co-owner of Hampton Lumber. “We’d be affected directly and indirectly through increased utility and supply costs. It’s a poorly conceived measure that will hurt our business and consumers throughout the state.”

The kicker about Measure 97 is that it’s a tax on total sales, not profits. That’s kind of like a waiter being taxed on the total bill of the meal he serves, rather than the tip he receives. For high-volume, low-margin products, there’s very little room to absorb the tax. By taxing sales rather than income, companies would have to pay the tax, even if they don’t make a profit.

“That’s the biggest downside for us – the fact that we’d have to pay the tax even if we were losing money,” Roseburg Forest Products President and CEO Grady Mulbery said. “Our industry is very cyclical – we go through lots of ups and downs. Roseburg has enjoyed some decent years as we’ve emerged from the recent recession, but we still have not recovered the losses we incurred as we kept plants running and kept our employees working as much as possible. Our ability to do the same in a future downturn would be severely hampered by this additional tax.”

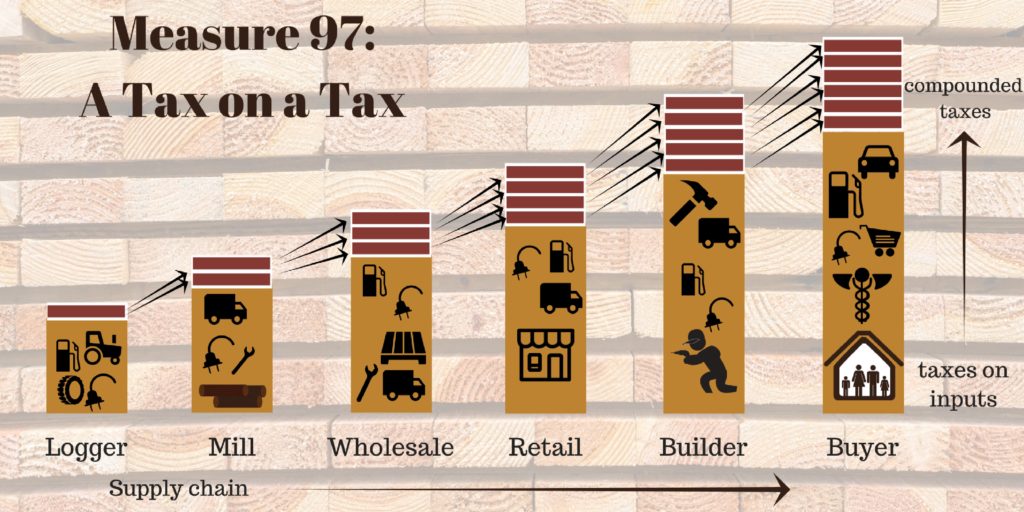

To truly understand the compounding effect a gross receipts tax like Measure 97 would have on the timber products industry, and ultimately the consumer, it’s important to follow a product along the complex supply chain from forest to frame. Every time the product changes hands is a new opportunity for a 2.5 percent tax as a result of Measure 97.

The first step starts in the woods with a logger harvesting timber. Andrew Siegmund is the third-generation owner of Siegmund Excavation and Construction, a road construction & logging contractor that has been operating in northwest Oregon for over 40 years. His company is hired by landowners, like Hampton, to build roads, harvest timber and deliver it to the mills. “We’re not a C corp,” Siegmund said, “but every business we do business with is, from fuel suppliers to parts and services, to equipment dealers and insurance companies – across the board. That’s pretty tough, our costs will be higher, but customers like Hampton are not going to be excited to have a conversation about increasing rates to offset that cost because they’re getting hit too.” Siegmund agreed that the only way his company could deal with the tax would be to freeze wages and benefits, lay-off employees, or pass the cost on. “We can’t move, and we can’t wring any more efficiency out of our operations. We’ve made considerable investments in machinery and technology to be as efficient as possible, we’re operating at the cutting edge.

The first step starts in the woods with a logger harvesting timber. Andrew Siegmund is the third-generation owner of Siegmund Excavation and Construction, a road construction & logging contractor that has been operating in northwest Oregon for over 40 years. His company is hired by landowners, like Hampton, to build roads, harvest timber and deliver it to the mills. “We’re not a C corp,” Siegmund said, “but every business we do business with is, from fuel suppliers to parts and services, to equipment dealers and insurance companies – across the board. That’s pretty tough, our costs will be higher, but customers like Hampton are not going to be excited to have a conversation about increasing rates to offset that cost because they’re getting hit too.” Siegmund agreed that the only way his company could deal with the tax would be to freeze wages and benefits, lay-off employees, or pass the cost on. “We can’t move, and we can’t wring any more efficiency out of our operations. We’ve made considerable investments in machinery and technology to be as efficient as possible, we’re operating at the cutting edge.

The challenges facing Siegmund are not uncommon. The nonpartisan Oregon Legislative Revenue Office issued a report on the potential impacts of Measure 97 and estimated that 38,000 private sector jobs would be lost as a result of Measure 97.

After a logger delivers the logs to the sawmill, Hampton Lumber processes the logs into lumber and residuals. When they sell these products to their customers, a 2.5 percent sales tax is generated. Incidentally, Hampton Lumber also has an Oregon wholesale business, so when they sell lumber between their mills and their wholesale business, they’ll pay an additional 2.5 percent tax. You can easily see how the compounded cost from taxes associated with inputs to the logger, the mill, and the wholesale operation (electricity, trucking, repairs, supplies) will pile up. The wholesaler then sells the lumber to a retailer, then to a home builder, and eventually to a buyer who, as the last stop in the supply chain, will ultimately pay a higher price for a home when the entire supply chain passes the compounded cost down-stream. In that way, Measure 97 is worse than a simple sales tax, which Oregonians have voted down nine times.

Measure 97 would hit business operations but it would also impact families directly through increased prices on everyday items like groceries, utilities, fuel, and clothing. The Oregon Legislative Revenue Office report estimated that the tax would cost Oregon households between $372 and $1,282 per year as a result of higher prices and other impacts. For example, Measure 97 would cost a family making between $48,000 and $68,000 annually $613 per year.

The very worst part about Measure 97 is that in the end, there’s no guarantee the money raised by the tax would go to education or anything else. Proponents of the measure are trying to convince voters that the money would be dedicated to a few specific things, but that’s just not the case. The money will go into the General Fund and the Legislature could spend the money any way it sees fit. It’s a bad deal for Oregonians all around.