More than 40 million tree seedlings are planted in Oregon’s forests each year, but growing a successful forest doesn’t start and end with planting a tree. In the same way a backyard gardener doesn’t just stick a tomato plant in the ground and come back two months later to juicy tomatoes, foresters, just like farmers, do much more to ensure that their seedlings have what they need to grow up healthy, productive and strong.

The Oregon Forest Practices Act, a set of laws that regulates activity on Oregon’s forestlands, not only dictates that landowners must replant new trees within two years of a harvest, it also requires that the young trees must be “free-to-grow” within six years of harvest. That means foresters have to guarantee the new trees are vigorous, well-distributed, and ready to grow successfully into a young forest.

The first few years of weed-free growth are the most important. Wilbur-Ellis demonstrated the difference with an 18-year trial of two sites, one planted with trees after a single treatment of herbicide and one planted without treatment. After just two years, the difference is visible above (tree from treated plot on right.) After 18 years, the treated site had trees that were 27 percent taller and 39 percent greater in diameter.

Small tree seedlings need light, water and nutrients to survive and grow. The biggest threat to the survival of baby trees is faster-growing weeds that steal these resources away from the tree. One way foresters give newly planted seedlings a jump on weed pressure is to apply herbicides to the site before the seedlings are put in the ground. One or two applications of herbicides is all that is needed to hold back the weeds long enough for a new forest to establish. Following establishment, the new forest won’t need further herbicide treatments for an entire generational rotation of 40-60 years.

“Nature abhors a vacuum,” says Bruce Alber, certified forester and sales representative for Wilbur-Ellis Company. “After a harvest, seeds from non-native invasive species like Scotch broom, Japanese knotweed, and blackberries get blown in or are carried in by animals.” Those, combined with grasses and other brush, grow quickly and develop vigorous root systems that out-compete and choke out conifer species. “Seedlings need at least 20 percent or less ground cover around them to grow and succeed,” Alber said, “The first few years of weed-free growth are the most important to their survival.” After the first few years, seedlings are tall enough to shade out competing weeds.

Western Helicopter applying herbicides on unit of land owned by Starker Forests.

While sometimes it makes sense to apply herbicides with a hand crew on the ground, application by aircraft (usually from a helicopter) provides a number of advantages. “Aerial application is extremely efficient in treating a large number of acres in the limited time available when the weeds and brush are susceptible and the crop trees won’t be damaged,” Alber said. “This window of opportunity can be a matter of a week or ten days for a specific unit and weed species. For a treatment project of 1500 acres, it might take a helicopter crew four to ten days, compared to about 300 man days for a hand crew.”

Western Helicopter president Rick Krohn, left, with Director of Maintenance Karson Branham. Western Helicopter owns eight helicopters (ranging in cost from $300,000 to $1.2 million) that costs about $1,200 per hour to fly. Branham is in charge of monitoring and repairing the multitude of parts and pieces of the aircraft that are regulated by the FAA. He estimates the helicopters take about an hour of maintenance per hour of flight.

Rick Krohn is the president of Western Helicopter Services, which has operated in the Pacific Northwest since 1966 and is one of the only aerial application services that specializes in forestry. In addition to increased efficiency, he explained that aerial application also reduces cost, the amount of chemical used, and risk to the applicator. “There’s no way a ground crew could cover all the acres for a forestry company, so they’d suffer more tree mortality and have to re-plant more,” Krohn said. “It would cost at least three times as much. Ground applicators also tend to put on more chemical per acre and there’s much more potential for applicators to suffer physical injury just from walking through all that brush.”

Technological developments in aerial application for forestry have considerably increased application precision in the last 30 years. “When aerial application in forestry first started in the late 1960s,” Krohn said, “the technology was nowhere close to where it is today.” Both Krohn and Alber agree that the most impactful innovation for the industry has been research on spray nozzle size and angle that results in increased droplet size for the product coming out of the spray booms (the arm of the aircraft that releases the herbicide).

“A lot of people thought that we needed to have small droplets to get good control,” Alber said. “We have shown that to be untrue, so we get more precise deposition onto the target and have virtually no off-target drift.” Larger droplets are heavier and reach the target area without being blown around. “The good thing about herbicide use in forestry is you usually only need a few drops to be effective,” Krohn said.

Advancements in research on how nozzle size and angle mitigate drift have been real game changers for the industry. There are more than 50 different nozzles for use in aerial application.

One of the key areas of research focus for the USDA Aerial Application Tech Research Unit (AATRU) in College Station, Texas is spray drift mitigation. Using a wind tunnel to simulate real conditions, scientists have created Aerial Spray Nozzle Models that allow applicators to determine the best nozzle size, nozzle angle and droplet size to greatly reduce the amount of small, driftable droplets. “New herbicide labels are now setting the requirements for droplet sizes and usually require medium or larger droplet sizes,” Alber said. “This allows us to cut a hard line between vegetation control and no damage to vegetation, protecting buffered areas such as waterways, neighbor boundaries, and other no-spray areas.”

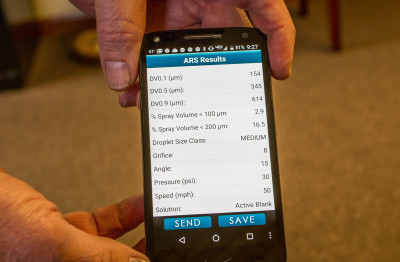

Mobile apps allow applicators to check nozzle size, angle and droplet size on site.

While on site, applicators can use a mobile app to look at how changing the parameters of the spray set up impacts droplet characteristics. “Small changes can make a big difference,” Alber said.

A key piece of knowledge that came out of the AATRU was discovering that “flying low doesn’t always mean less drift,” said Krohn. “Because we’re using such large droplets, it was actually found that flying ten feet or lower increases the amount of driftable droplets because the wind vortices from the wings or blades of the aircraft push the droplets further than flying at 18 feet.” Krohn explained that flying higher actually allows the droplets to mix with the air and separate for better efficacy.

Another recent improvement in aerial application is the incorporation of Global Positioning Systems for alignment and guidance from the cockpit. By keeping a mounted tablet in the pilot’s peripheral vision, the pilot can watch the spray path in real time, reducing overlap and increasing accuracy and precision. “GPS guidance systems also offer a very good record,” Krohn said. “Before GPS we were still doing a good job, but the technology gives a level of comfort – it gives a record of where and when the boom has been turned on.” The use of shorter booms also reduces the chance of droplets getting pulled upward by the vortices created by the rotor blade, and half-boom capability (literally turning half the boom off) allows for better precision around stream buffers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=85xlgRehZiQ

The above video is a sped-up version of the spray path the pilot sees in real-time from a tablet in the cockpit (the actual application took 45 minutes). A sensor on the boom is triggered when the spray is switched on. Stream buffers are sprayed first with the half boom setup, the blue lines indicate when the half boom is on, while the red lines are when full boom is in use.

Krohn also noted that the introduction of new pesticides or formulations of pesticides that are more environmentally friendly and require less product to be applied has made a big impact in the industry. “Thirty or 40 years ago we used the same herbicide to treat everything,” Krohn said, “But now we can assess the weed pressure on a given site and tailor applications for specific treatments so we’re not putting on any more than needed.” Drift reduction technology products that are added to the spray mix can also be useful in some applications to further reduce the fine, driftable droplets and focus more herbicide on the intended target.

The future of aerial application promises even more innovation as technology advances. Drones and unmanned aircrafts are being tested for potential use in certain instances of pesticide application and have shown to be useful in small areas in Japanese agriculture. The technology isn’t quite there yet for commercial use in the U.S., though. “The problem with small aircraft is that they can’t carry enough spray mix to spray more than a small fraction of an acre, much less a 70-acre patch of Scotch broom,” said Alber. They may have other uses though. “Drones or multirotor unmanned aircraft could be useful in scouting forest sites for weed density and possible weed identification,” said Alber. “Agriculture is using them now for remote sensing on crops.”

Reducing drift is a the primary driver of innovation in aerial application for a number of reasons, only one of which is the simple fact that the cost of the chemical applied is the single most expensive part of aerial application and every drop that ends up outside the target area is money wasted. Aerial application is a vital tool for sustainable forest management, and while foresters take tremendous care to ensure that weather conditions are right and all rules, regulations and best management practices are followed, technological advancements have revolutionized the accuracy and precision of this industry.